Chapter 16. Subnational Boundaries

We look now at a comparatively minor subject, the political subdivisions of nations or, in other words, at states and counties in the U.S. and at their foreign equivalents.

It’s taken us a long time to get back to third grade, hasn’t it? Nearly every American child is expected to learn the 50 states. There usually remain a few stinkers. Some students confuse Ohio with Iowa. Others can’t remember if Vermont is east of New Hampshire or whether it’s the other way around. Many can’t name the three states that share the peninsula between Chesapeake Bay and Delaware Bay, though the name Delmarva Peninsula gives you the answer. Is this critical knowledge? No, but ignorance of it can be embarrassing. Is that sufficient reason to know that Alabama is east of Mississippi? I don’t know.

Just about everyone knows that the states of the West are generally larger than those of the East and that boundaries in the West tend to be straight.

Occasionally, even in the West, rivers are made to serve as state boundaries, as here with the Colorado below Hoover Dam.

Occasionally, mountains are called in, as here with the gray line along the summit of the Bitterroots, with Idaho on the west and Montana on the east. County lines in both states (in green) naturally terminate at the gray line. Some of those county lines run straight but others hug mountaintops, like Granite County at the lower right. Mountains are conveniently visible and often better suited to serve as boundaries than straight lines, but simplicity is attractive..

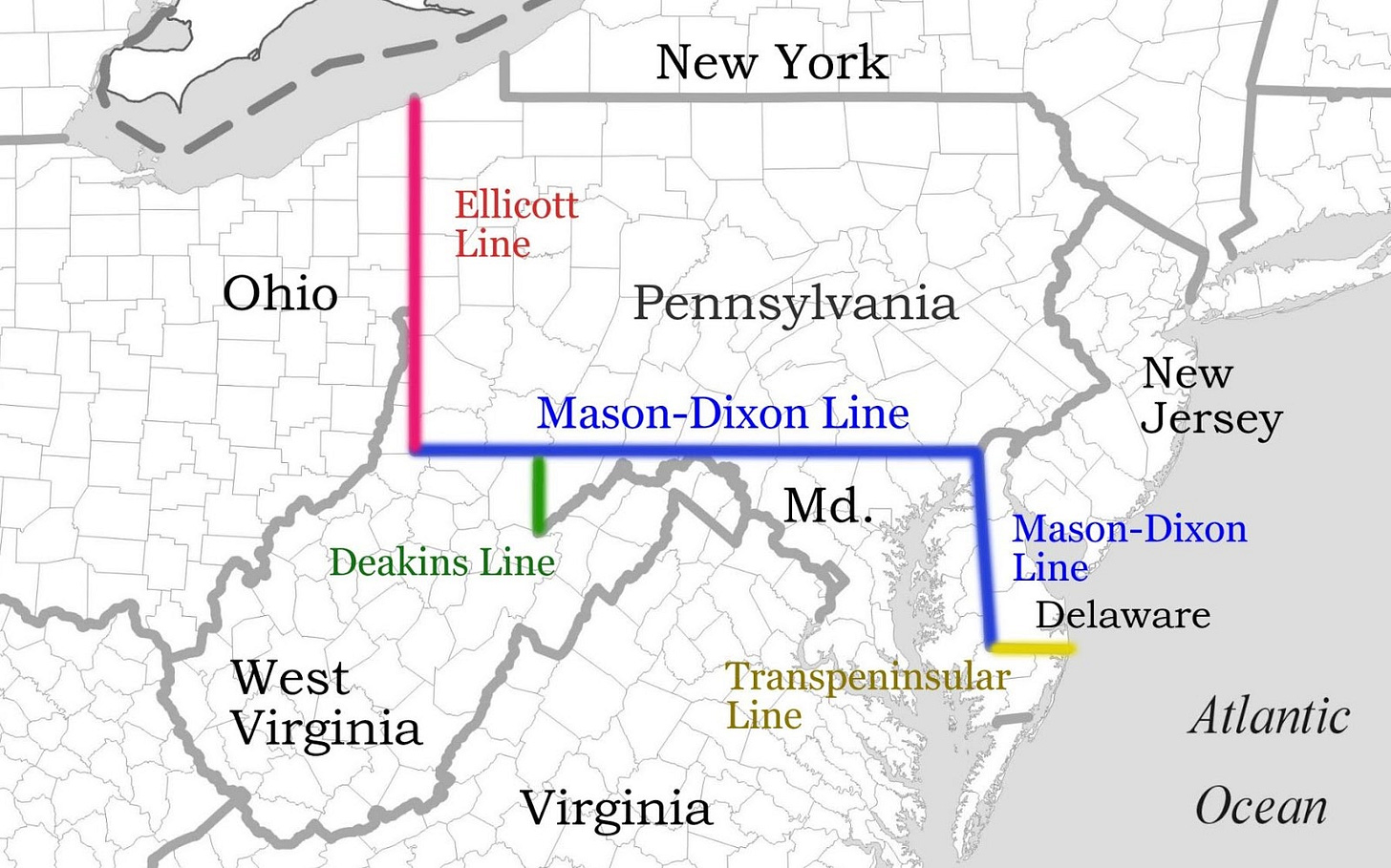

The eastern states do have some straight lines. The most famous is the Mason-Dixon Line mostly forming the southern boundary of Pennsylvania and, because there were no slaves north of it, often thought of as the boundary between the North and the South. It may come as a surprise that Mason and Dixon were both Englishmen, but the line was drawn in the 1760s when this part of the world was still run by the British. Mason stayed on this side of the water until his death in 1786, Dixon went back home.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mason%E2%80%93Dixon_line

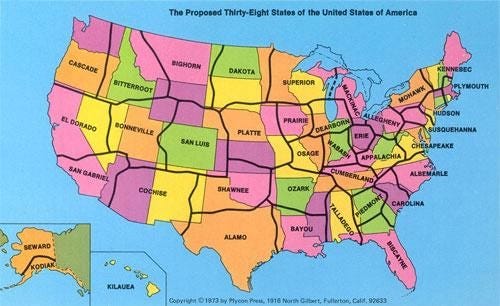

Many of these boundaries would not exist if we were starting over. Here are two proposals to revise them, one from the 1970s and the other more recent. They are designed so each state has about the same population (a little over six million in the newer map). Sounds democratic—much fairer than giving Wyoming (population 600,000) and California (population 39 million) the same number of senators. Likelihood of any such reform? Near zero.

Here’s a recent proposal to carve up California. This would have the people of the former state 12 senators, but the proposal didn’t get enough signatures to qualify for the ballot in 2016.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Six_Californias

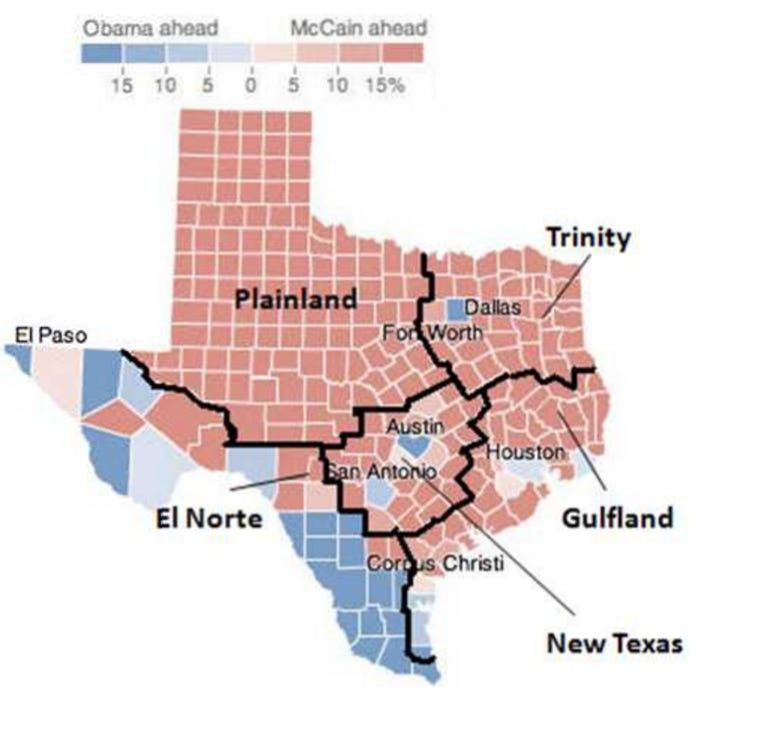

Here’s a proposal to split Texas in a way that reflects voting behavior. Don’t hold your breath.

http://bigthink.com/strange-maps/537-whats-the-plural-of-texas

We’re more inclined to celebrate what we have, like Old Red, now a museum but built in 1890 as the Dallas County Courthouse.

The Oklahoma State capitol was finished in 1917, but the $20 million dome had to wait until 2001. The color doesn’t quite match. That’s because, unlike the building, which is stone, the dome is precast concrete.

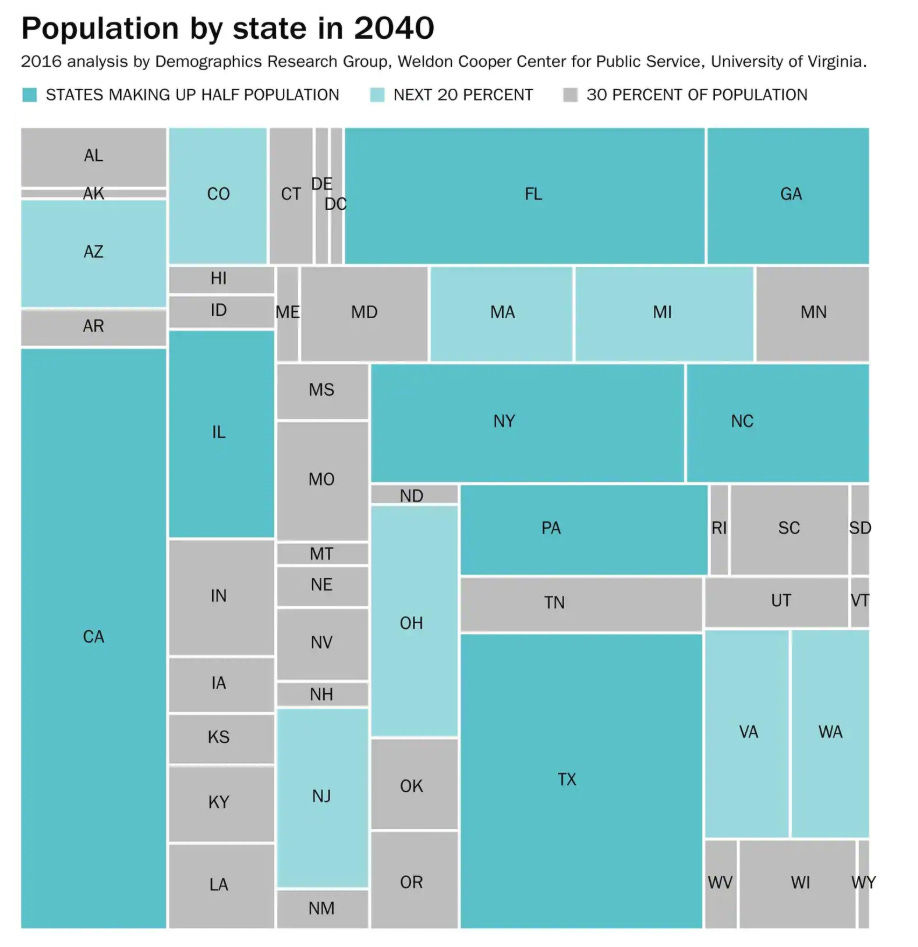

Twenty years from now, half of all Americans will live in eight states but will have only 16 out of the 100 votes in the senate. The voters in the 42 other states are much whiter and much more Republican, and they’ll have an easy job blocking the will of the majority. It’s a great gig if you’re white and Republican; it seems grossly unjust if you’re not.

Is there a justification for the existing arrangement? Sure: it’s that the Constitution would never have been adopted if the states with smaller populations had not been guaranteed equal standing with more populous ones. Could we change that guarantee? Sure, but only by amending the constitution, which holds in Article V that “no State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of its equal suffrage in the Senate.” Implication: you’d have to persuade 38 states to ratify an amendment providing more equal representation. Good luck with that.

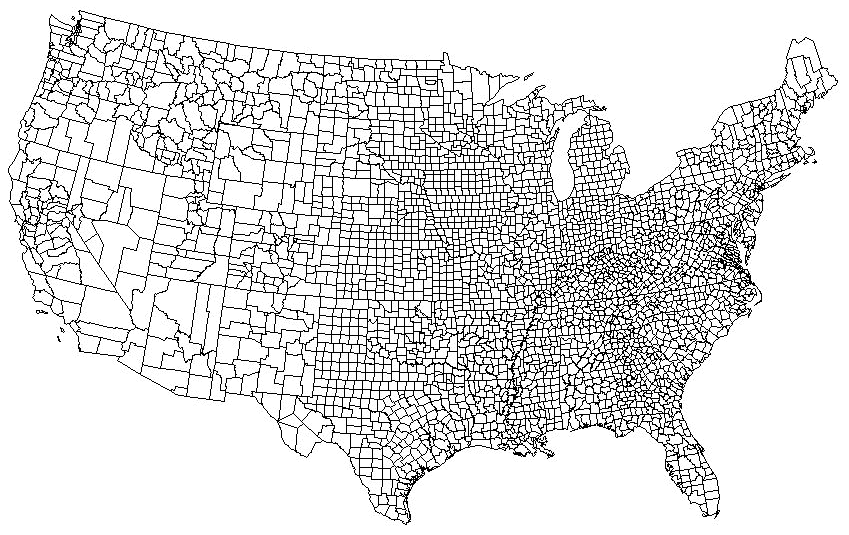

The U.S. is further subdivided into more than 3,000 counties. (Those in Louisiana are called parishes, and those in Alaska are called boroughs.) The largest ten are west of the 100th meridian. The biggest counties east of that meridian rank 30 and 31; they’re St. Louis County (including Duluth, Minnesota) and Aroostook County, in far northern Maine.

The simple explanation for this disparity is that the west is dry and therefore sparsely populated. Sure, there are exceptions. Coastal Washington and Oregon are wet enough to have been settled in the 19th century with modestly sized farms: you didn’t 1,000 acres to survive. There are small counties in Mormon country, too. It’s dry there but the Mormon settlers developed irrigation works. Another exception: small counties in the old gold rush areas of the Rockies and Sierra Nevada.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_the_largest_counties_in_the_United_States_by_area

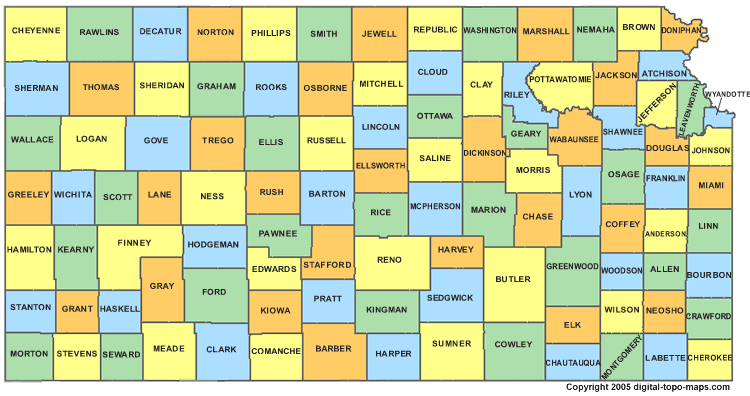

Some states organized their counties very tidily. Here, for example, is Kansas. Apart from its state boundary with Missouri, which hugs the Missouri River, the only deviation from straight lines and right angles is the western edge of Pottawatomie County and some of its eastern neighbors, all of which follow Missouri tributaries.

http://www.digital-topo-maps.com/county-map/kansas.shtml

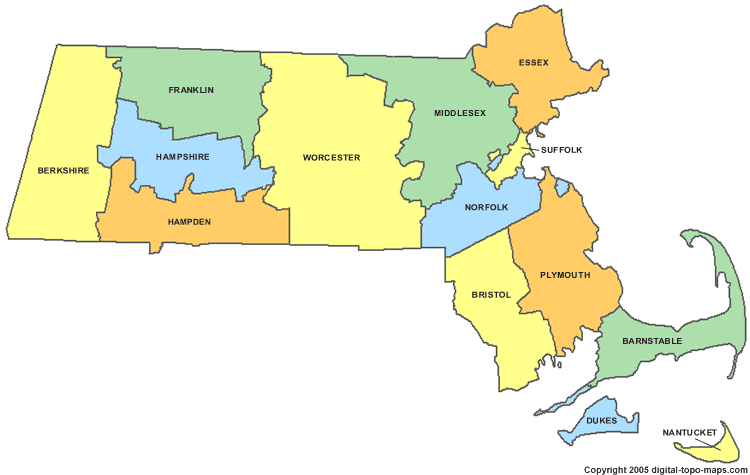

Compare that with Massachusetts, where there are almost no straight county lines except at the state’s edge.

http://www.digital-topo-maps.com/county-map/massachusetts.shtml

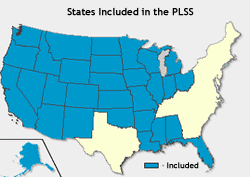

The explanation goes back to the public-land surveys. Here’s a diagram reminding you how the scheme worked. A baseline and principal meridian, shown here at the upper right, are surveyed. From those two original lines a grid is constructed. The cells are called townships and run about 23,000 acres (36 square miles). The middle diagram shows a single township subdivided into 36 sections (that’s the formal or technical name for them), each one measuring approximately one square mile, or 640 acres. The sections are numbered in an idiosyncratic but standardized way. The lower-left diagram shows one section and its standard subdivisions. Land-run participants in Oklahoma got 160 acres, a quarter-section.

http://nationalatlas.gov/articles/boundaries/a_plss.html

Here are the states that were part of the public land survey system (PLSS). Another way of saying this: these are the places where rural roads behave (I mean that they go in straight lines because they follow section lines).

https://nationalmap.gov/small_scale/a_plss.html

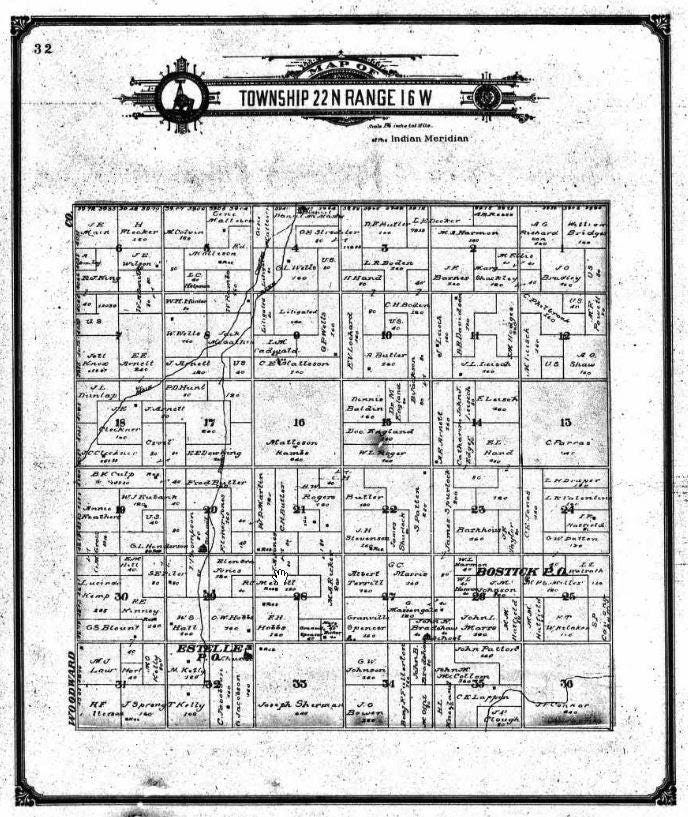

Here’s a 1910 map of part of Oklahoma’s Woodward County. The map shows one township and its original (or near original) settlers.

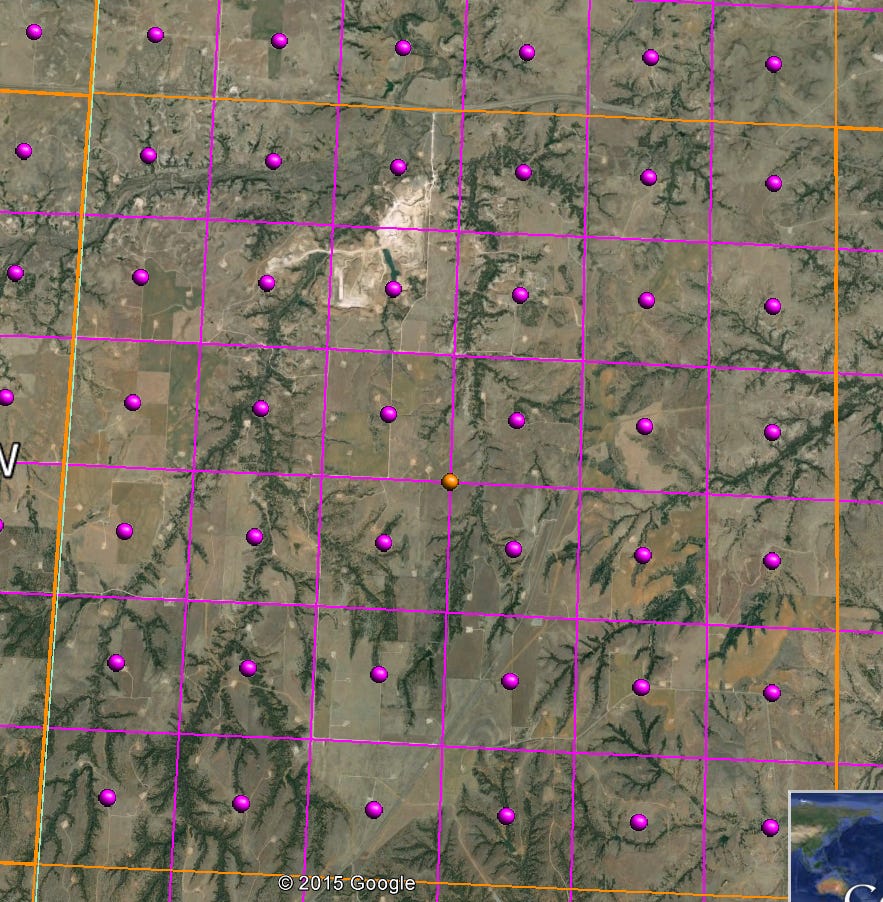

Here’s the same township today. Section lines are in purple, township lines are in orange, and county lines are in green. (In this case the green line separates Woodward County on the west from Major on the east.) In laying out the county boundaries, the authorities just followed the township lines.

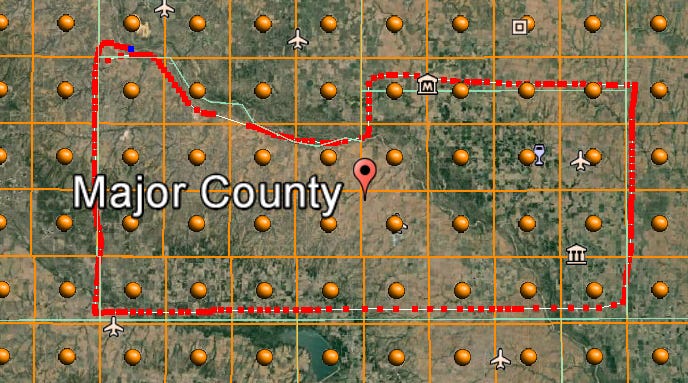

And here’s Major County in its entirety. The perimeter is all township lines except where it follows the Cimarron River. (The red line wobbles a bit; blame my hurried hand.)

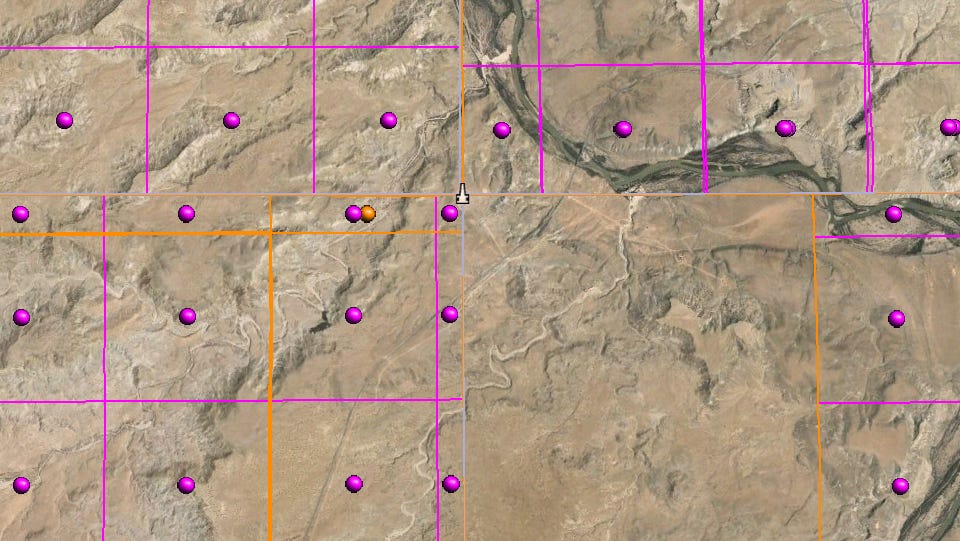

Here’s the famous Four Corners, where Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico touch. The map shows the monument there, just north of the center. Notice that it’s also a township corner. Some of the adjoining sections in New Mexico have never been surveyed. The townships at the north edge of Arizona are truncated because at the state line Utah’s Salt Lake grid replaces Arizona’s Gila grid.

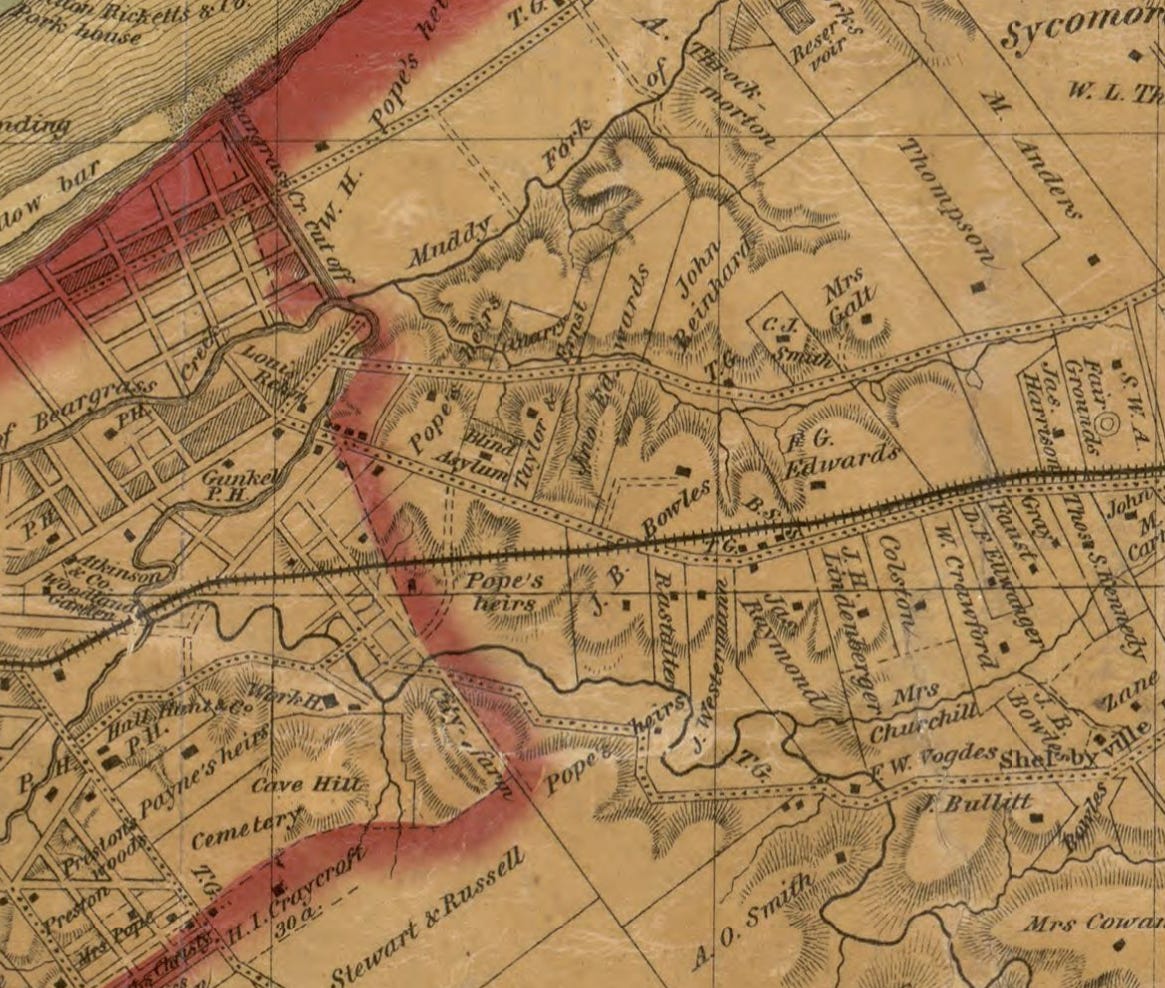

Compare these places with an eastern county, not part of the township and range system because the federal government never owned it. Here’s Jefferson County, Kentucky. See Louisville up on the river?

https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3953j.la000234/

I’ve zoomed in to the right edge of town, where properties have been surveyed in a so-called metes-and-bounds system. “Metes” refers to straight lines between defined points, such as a road junction or a big tree. “Bounds” refers to lines atop natural features, such as a creek or ridge. The properties here facing the south side of the railroad track have boundaries that are partly defined by metes and partly (along the creek) defined by bounds.

Now you see why Kansas is tidy and Massachusetts isn’t: one was subject to the federal government’s survey system, and one wasn’t. There are lots of puzzles, however. Here’s one: Texas. How come so many counties are irregular? The answer is that Texas, uniquely among the Western states, was never part of the U.S. public domain, so it surveyed its own lands. (That was part of the deal when Texas entered the Union: it kept its land.) Late in the 19th century, the state decided to adopt a federal-style grid for its last-to-be-settled western counties. Texas, by the way, has more counties than any other state.

http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/texas/texas-county_outline-2010.pdf

Here’s California, which should have nicely rectangular counties but mostly doesn’t.

http://www.digital-topo-maps.com/county-map/california.shtml

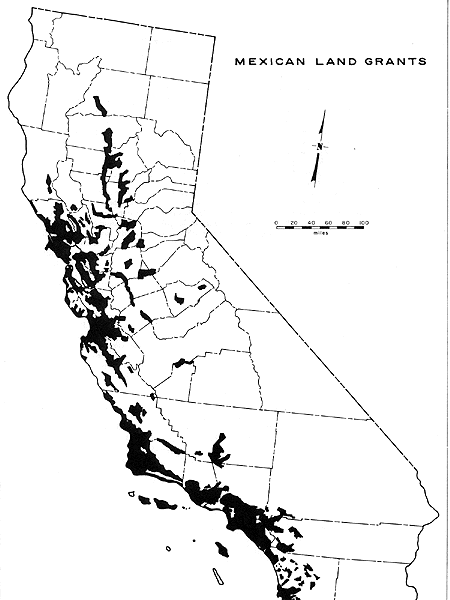

There are a couple of reasons for this. One is that much of the state before 1848 was owned by the men who held the 800 or so land grants issued by the Spanish or Mexican governments. They were allowed to keep their grants with the original grant boundaries. Areas covered by these grants were untouched by the public-land surveyors.

http://www.geog.ucsb.edu/~joel/g148_f09/lecture_notes/rancho_period/land_grant.gif

By the way, the same thing is true in New Mexico, where the grants cluster not only around Santa Fe but along the Rio Grande and Pecos rivers, which naturally attracted early settlers.

http://online.nmartmuseum.org/assets/files/Maps/LandGrants.pdf

The other reason for California’s irregular counties goes back to the gold rush of 1849, when miners rushed to the foothills stretching from North San Juan in this snip south to Placerville and beyond. The miners needed to be close to an office where they could file their mining claims. That meant counties had to be small. They could have been small and square, but there no survey lines yet, so the counties were organized in narrow strips corresponding to the watersheds of the streams running off the Sierra Nevada. Outside the gold country, the boundaries simply were straight lines, for example running east to Nevada.

Get that Old West feeling?

It’s been updated in ways that would puzzle the Forty-Niners. “Hank, what’s a bistro”

Are county boundaries any more democratic than state boundaries? The most populous county in California (Los Angeles County) has 10 million people, while the least populous (Alpine County) has 1,159. Both have two state senators. Not exactly what we think of when we say, “One man, one vote,” but try to change it!

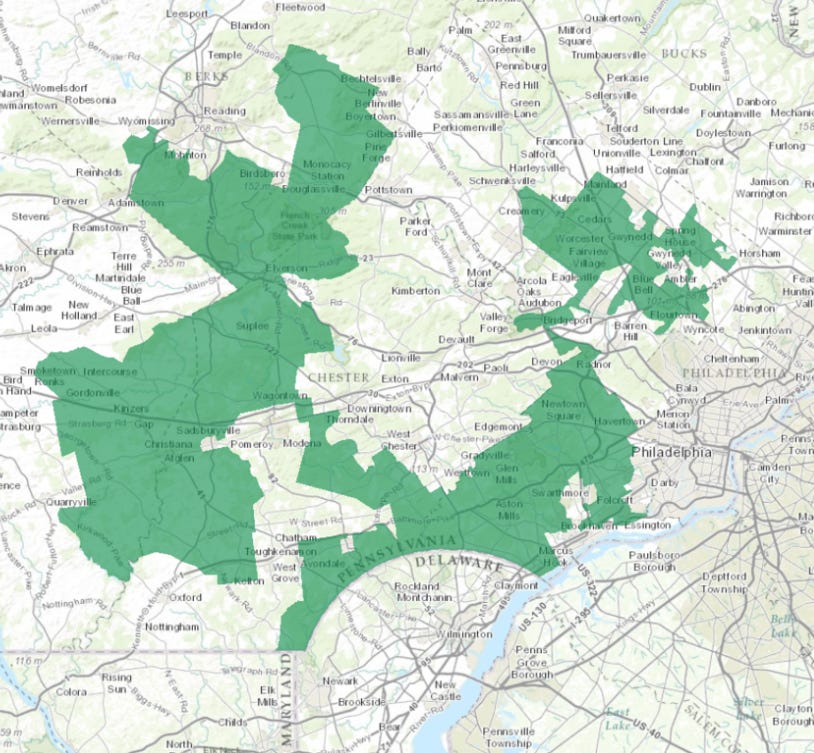

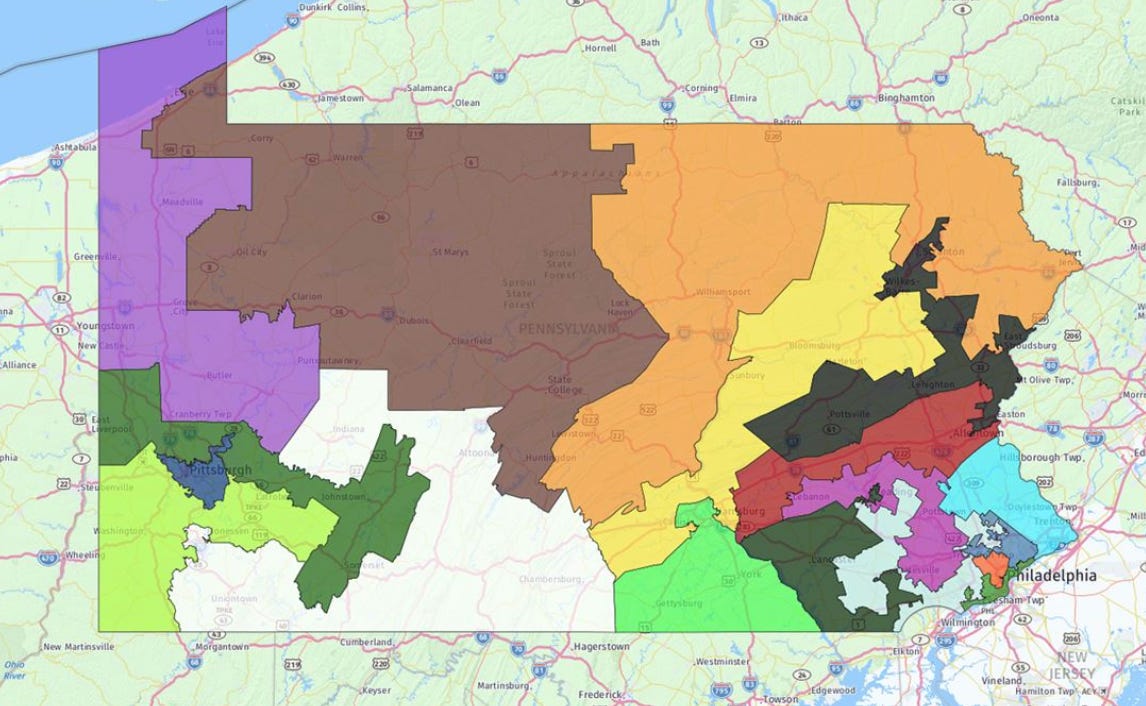

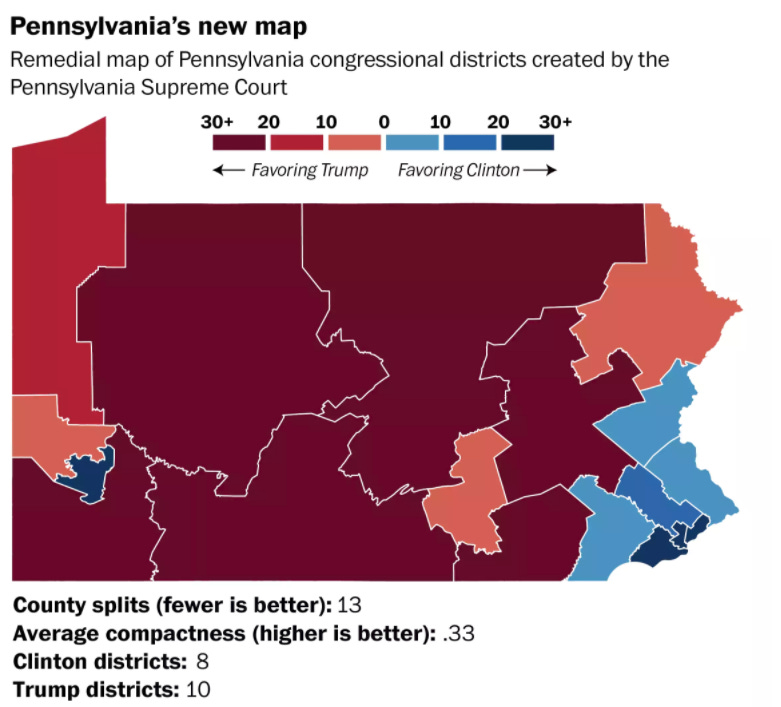

I guess I shouldn’t get too worked up about this. Take a look at the masterful job that legislators in 2013 did gerrymandering Pennsylvania’s Congressional District 7. The idea was to set up a district that Republicans couldn’t lose. All went well until somebody sued. The Pennsylvania Supreme agreed that the boundaries were unjustifiable, and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to get involved. (The outline has been described as Goofy kicking Daffy Duck. See it?)

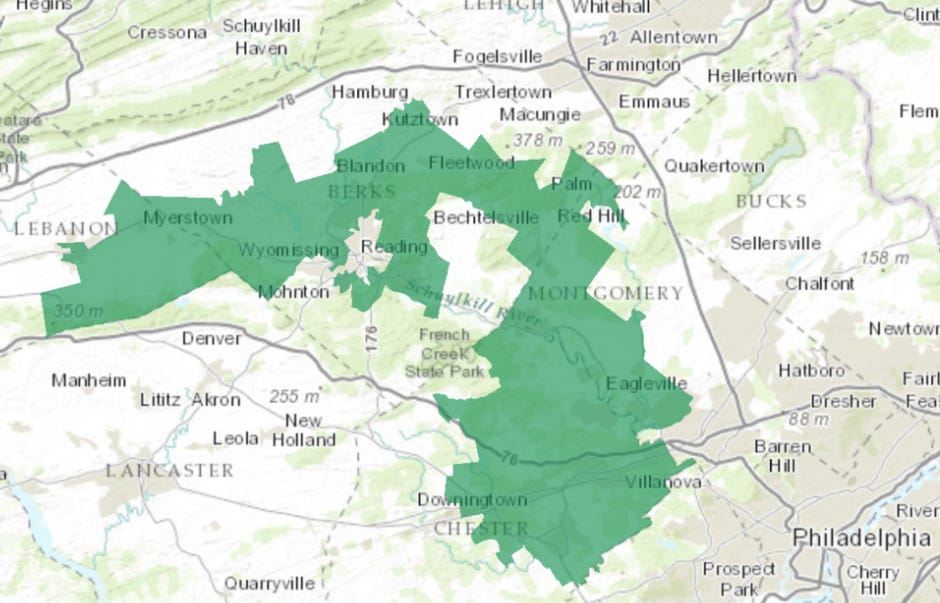

Here’s Pennsylvania’s District 6. People say it looks like a dragon attacking Philadelphia’s western suburbs. I’m not sure about that one.

Here’s the state map as it was.

Here’s the map imposed by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Republicans in 2018 failed in an effort to impeach the judges who imposed it.

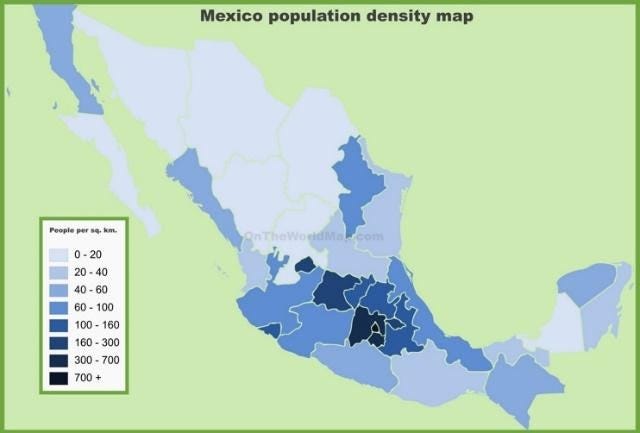

It’s time for another whirlwind tour of the world. As our states grow larger in the arid and less populous west, so, too, the states of Mexico grow larger to the less populous northern and southern states.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mexico_states_map_w_names.png

http://ontheworldmap.com/mexico/mexico-population-density-map.html

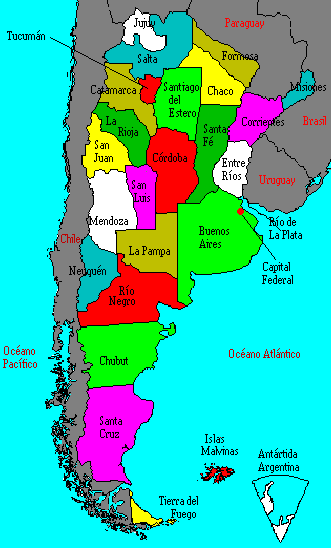

It’s the same story in Argentina, where states grow larger to the arid and less populous south.

http://www1.american.edu/ted/argbeef.htm

Canada has three small provinces in the east, six big provinces farther west, and three Arctic territories. It used to be two, but in 1999 the Northwest Territories was split to form the new territory of Nunavut, which is 90 percent Inuit (versus about 10 percent Inuit in the remaining Northwest Territories). The biggest previous change to the map came in 1949, when Newfoundland and Labrador joined Confederation. Until then, they--or it—had been an independent Dominion, like New Zealand.

There’s a perennial question about whether or not Quebec—which is bigger than Alaska and twice the size of Texas—should secede. Canada doesn’t seem the least willing to have a civil war to stop such a thing, but Quebeckers, though resolute in their devotion to their French language and culture, have yet to vote in favor of a split.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Political_map_of_Canada.png

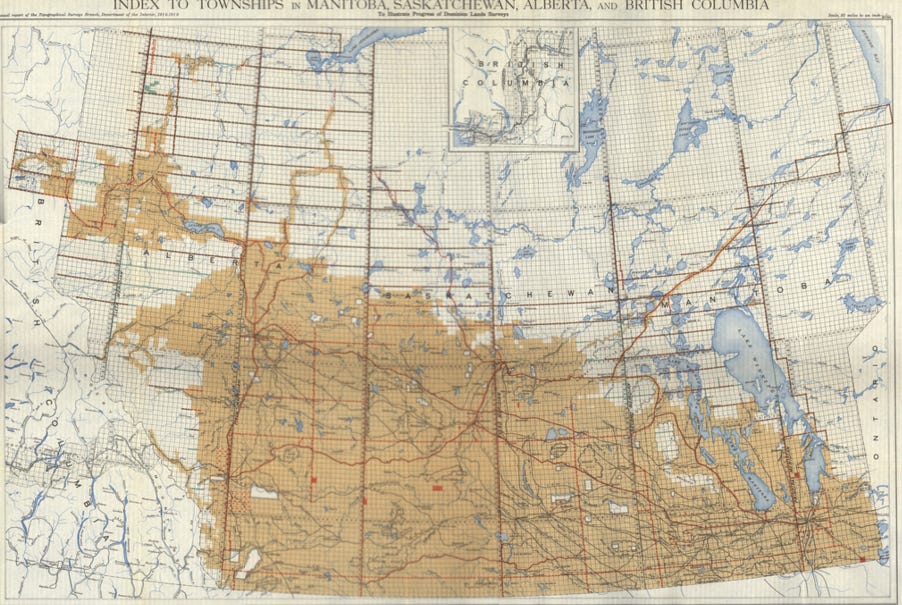

The boundaries of the three prairie provinces are as rectangular as those of our western states. That’s because Canada copied almost exactly the American public-lands survey. Here it is: the Dominion Land Survey, with a zillion townships, each 36 square miles.

Remember Fort McMurray near the Athabaska Tar Sands? It’s in township 89 North, range 10 W, Fourth Principal Meridian.

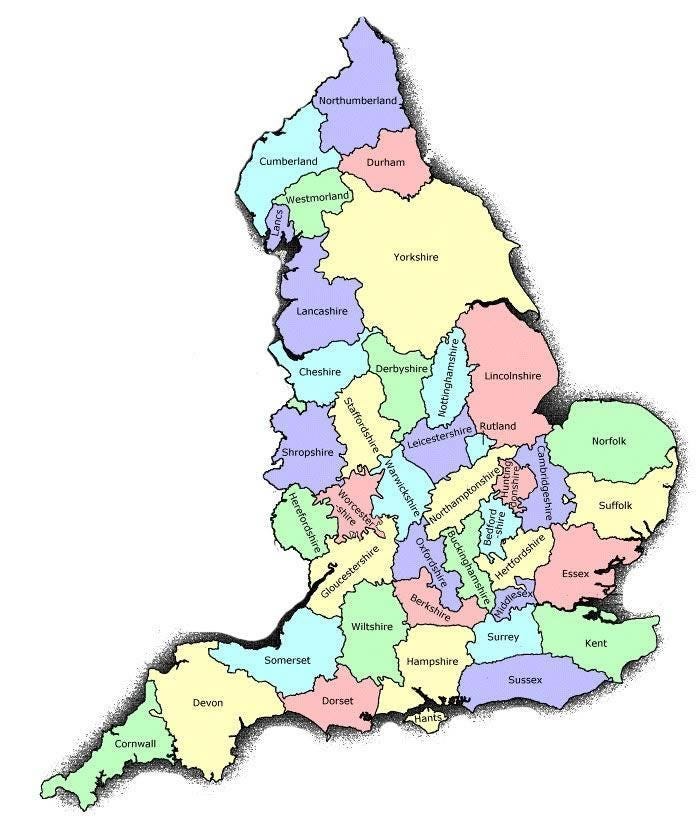

Let’s hop over to Europe and consider once again the question of stability and flux. For an example of stable boundaries, consider the UK, which has counties like the USA. They’re old, older even than the word “county,” which was imported by the French during the Norman invasion. See a pattern in the names? The –shire suffix indicates a name derived from a town, such as York, Lincoln, and Derby. The –sex suffix indicates a Saxon kingdom, as Essex, Sussex, or Middlesex.

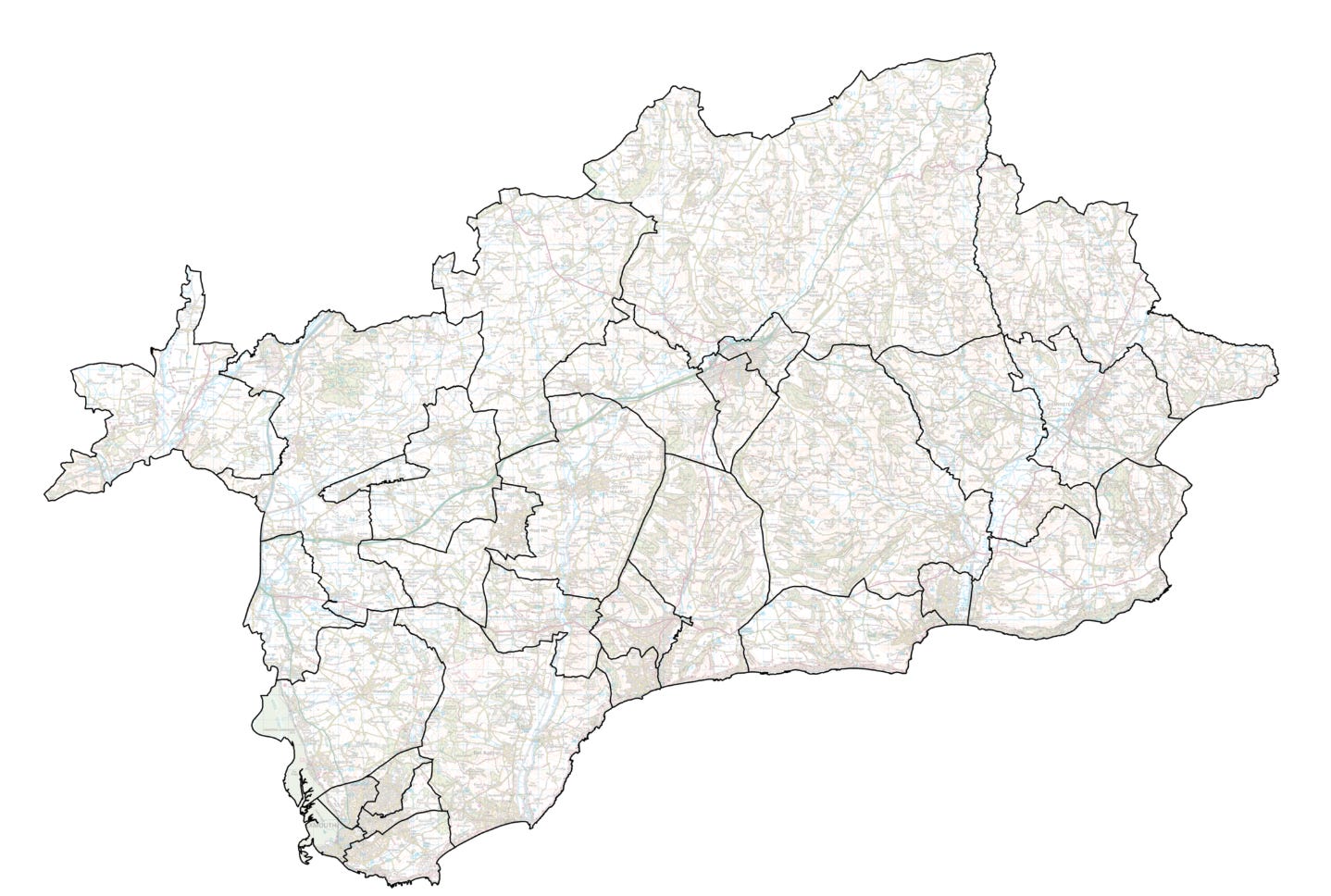

They’re also subvided, however, into 326 districts. Here’s the case of Devon. See East Devon?

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/07/England_Administrative_2010.png

East Devon is subdivided into parishes. The UK has over 10,000 of them, which amuses me because I think of all those students who go through their entire lives thinking that geographers know all the countries of the world and their capitals. By that logic, a university professor of geography should know all the counties of the United States and maybe all the parishes of the United Kingdom. Brilliant idiocy.

http://www.lgbce.org.uk/_flysystem/s3/2018-03/Drawing2.png

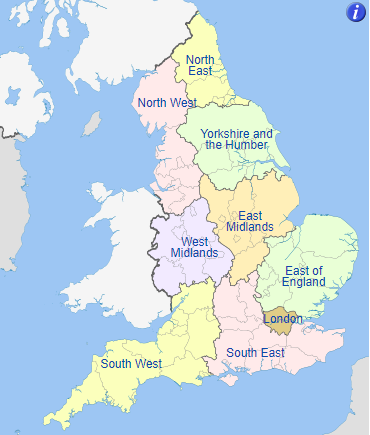

The British remain attached to these ancient names of counties, districts, and parishes, though for administrative purposes, the counties have been grouped since 1992 into nine regions and further subdivided into metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subdivisions_of_England

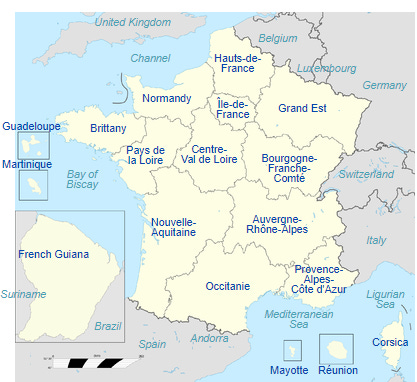

France has been much more willing than the UK to rationalize its political subdivisions. Here are its 13 administrative regions, which were created in 1982.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regions_of_France

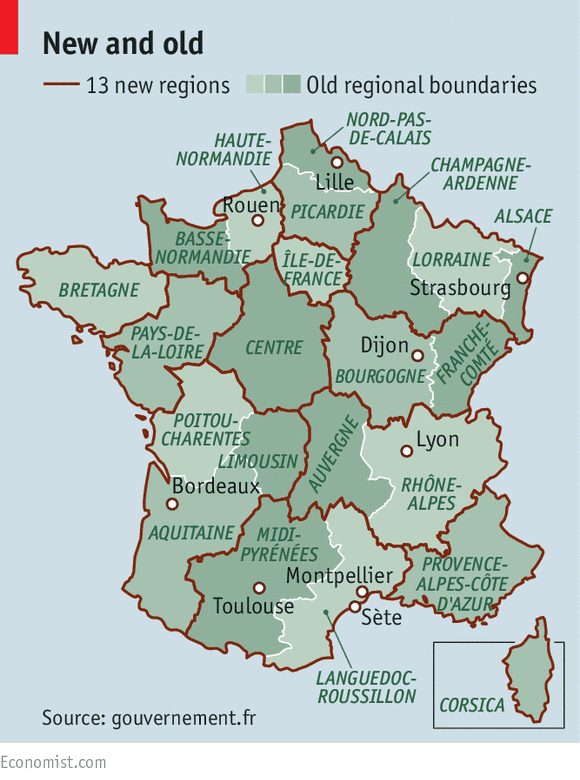

There used to be 22 regions. Down on the Mediterranean coast, Montpellier lost its status as the capital of Languedoc-Rousillon, and Toulouse became the capital of a consolidated region. Lots of people in Montpellier were unhappy, because the regional government’s payroll was $143 million in 2010. Will taxpayers save money? Doubtful. Civil-service jobs are protected.

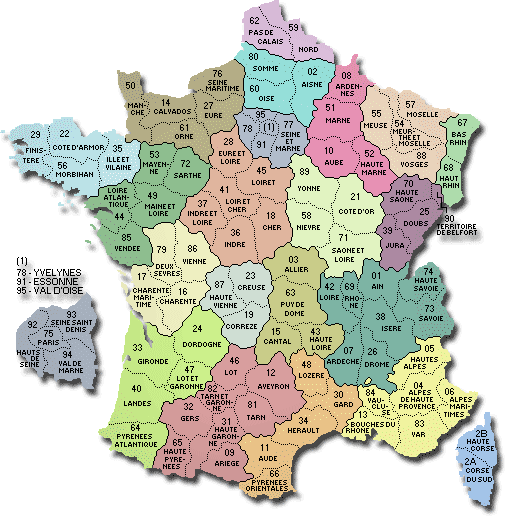

Such rationalization has a long history in France. The regions are subdivided, for example, into departments, roughly corresponding to American counties. The striking fact is that the 96 départements are almost all the same size, about 3,000 square miles. In theory, they’re small enough that a rider could reach from the center of each to the periphery in a day. In practice, the departments are larger than you might guess, however. The Gironde, down in the southwest, is not much bigger than its neighbors, but it’s bigger than Yellowstone National Park.)

Can you imagine how hard it would be to reorganize the U.S. into counties of a similar size? It would take a revolution. That’s exactly how it happened in France, of course. The provinces of the ancien régime were broken up in 1791 in a deliberate attempt to break up the old regional loyalties and replace them with a national one. (This map also shows the now-obsolete regional boundaries.)

http://www.map-france.com/departments/

You can see something similar happening in post-apartheid South Africa. Here’s the map of South Africa when it was created after the Boer War (1899-1902). There’s a huge, English-dominated Cape Province, mostly desert or semi-desert. To its east is the Orange Free State, which is on the Orange River and was “free” in the sense that the British for a time allowed the Boers or white Afrikaner farmers to run their own affairs. To its north is the Boer-dominated Transvaal, the region beyond or across the Vaal River. Natal, with the big port of Durban, was dominated by the English, like the Cape.

(The gray enclaves are Lesotho and Swaziland, British-ruled until 1968 but since then independent nations and members of the United Nations. Swaziland recently changed its name to Eswatini.)

In 1948 South Africa adopted a policy of apartheid, literally “separateness.” Here are the “bantustans” created at that time as so-called homelands for the black population of the country.

(Back about 1952 or 1953, a representative of the South African consulate came to visit my third or fourth-grade class. He seemed very well dressed and very polite, but there was a vague sense that he was attemping to justify something rotten. Our teacher didn’t say anything, so far as I recall. We just sensed it. I don’t know how or why.)

Here’s the map today. The “bantustans” were abolished in 1994. The Cape has been broken into sections. The Free State survives, though it’s no longer free in the historical sense and has dropped Orange from its name. The Transvaal is gone, replaced mostly by Limpopo and Mpumalanga—African names instead of European ones. Johannesburg now has its own province, called Gauteng (the “g” is pronounced “h,” so “Howteng”). Natal (yes, “Christmas,” because Vasco da Gama came by on Christmas Day, 1497) is replaced by Kwazulu-Natal. It’s a bit like the French Revolution. In this case it’s a black-majority government erasing a hated past.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Administrative_divisions_of_South_Africa

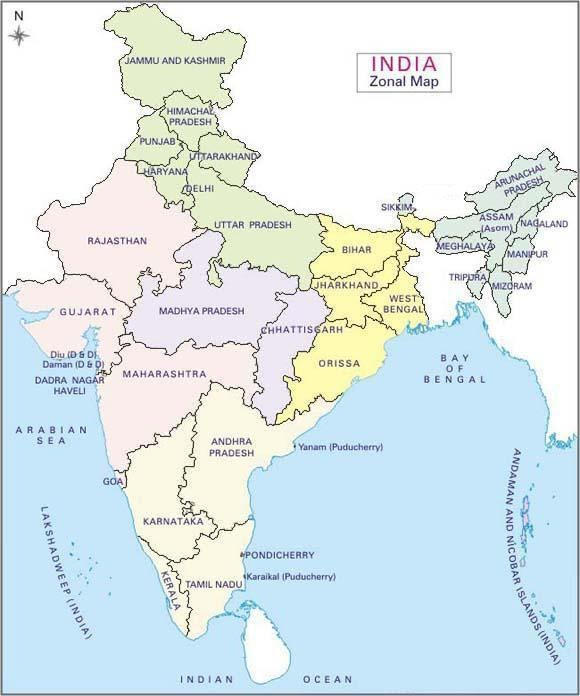

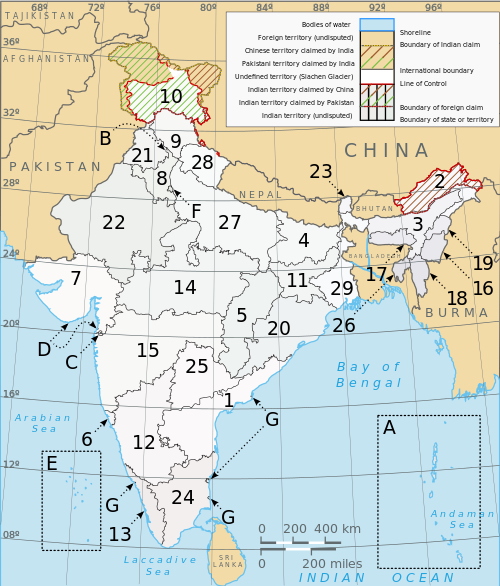

Three Indian states have over 100 million: they are Uttar Pradesh (which means “Northern State”), Maharashtra, and Bihar. Bihar is small—at 36,000 square miles it’s just a bit over half the size of Oklahoma—but Bihar has four times the population of Texas.

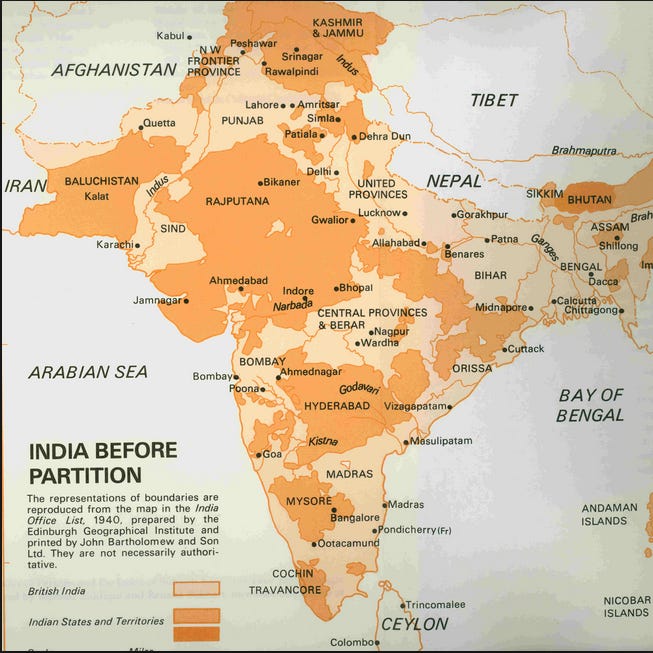

Now look at the map as it was in 1940. Instead of Uttar Pradesh you’ll find the United Provinces. (Nobody remembers what was “united,” but the answer is the provinces of Agra and Oudh, combined by the British in 1902. Conveniently, the abbreviation both before and after renaming was U.P., by which name the state is still colloquially called.) Instead of Maharashtra you’ll find Bombay (which was then a province as well as a city). Only Bihar existed then as well as now. Ironically, it’s one of the poorest states in the country. One indicator of this is that its capital, Patna has only 1.3 million people. Such a low degree of urbanization suggests an overwhelmingly rural place. The countryside is beautiful, green as can be, but that’s the perspective of someone who’s got plenty to eat.

The darker-colored areas are areas where the British allowed local princes (rajas and maharajas and more) to rule nominally; lighter colored areas were administered directly by the British. They include not only the crowded Ganges Valley but the country’s four chief cities: Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras.

After India became independent, in 1947, the princely territories were abolished and the country was reorganized into states whose boundaries corresponded more or less to areas sharing a common language. The language of Bihar is Bihari; of West Bengal, Bengali; of Tamil Nadu, Tamil; and so on.

Is this fissioning sensible? Good question, because it does seem to invite wasteful proliferation of government jobs. On the other hand, smaller states may actually work better than big ones. Here’s a 4-minute video that reviews the history of political reorganization of Indian states and argues that it’s probably a good idea.

http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2014/06/telangana-and-andhra-pradesh

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/India

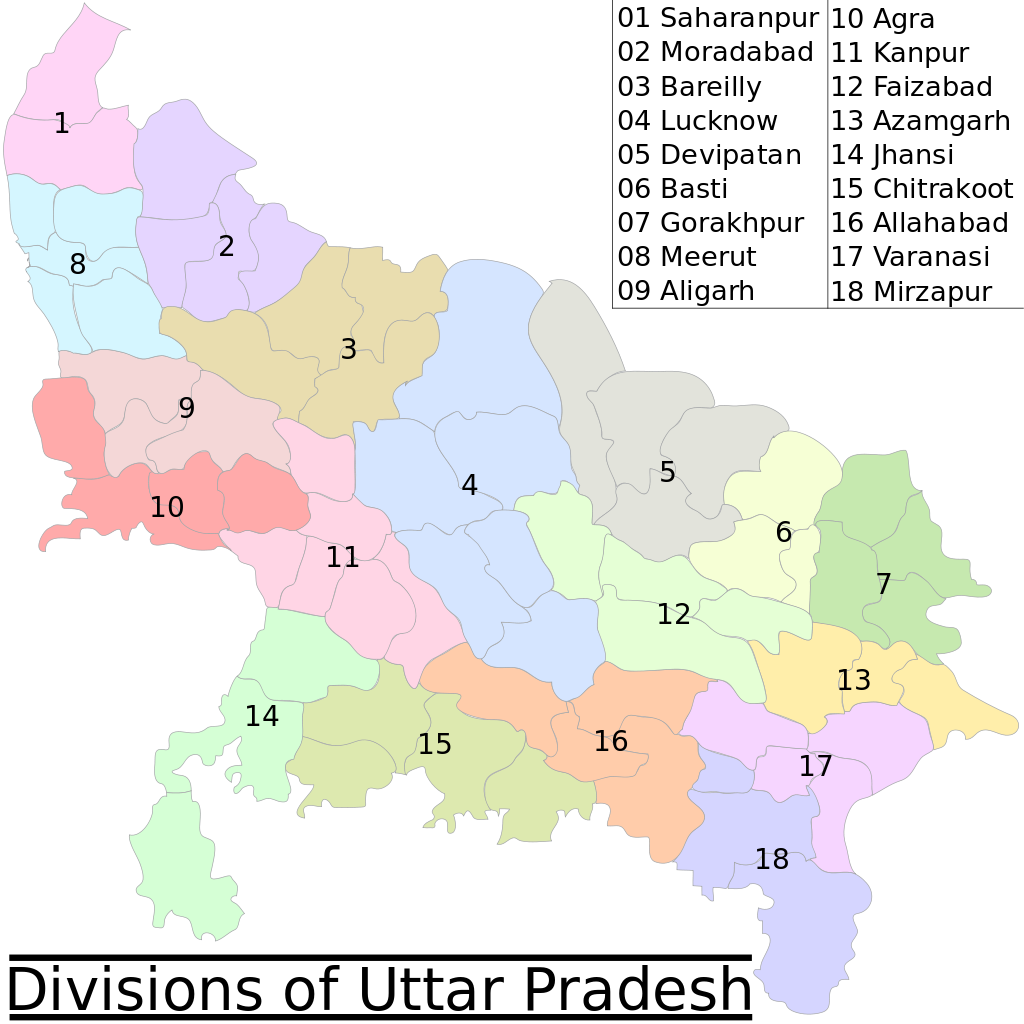

Does India subdivide its states? Of course. Here are the 18 divisions of U.P.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uttar_Pradesh#/media/File:Uttar_Pradesh_administrative_divisions.svg

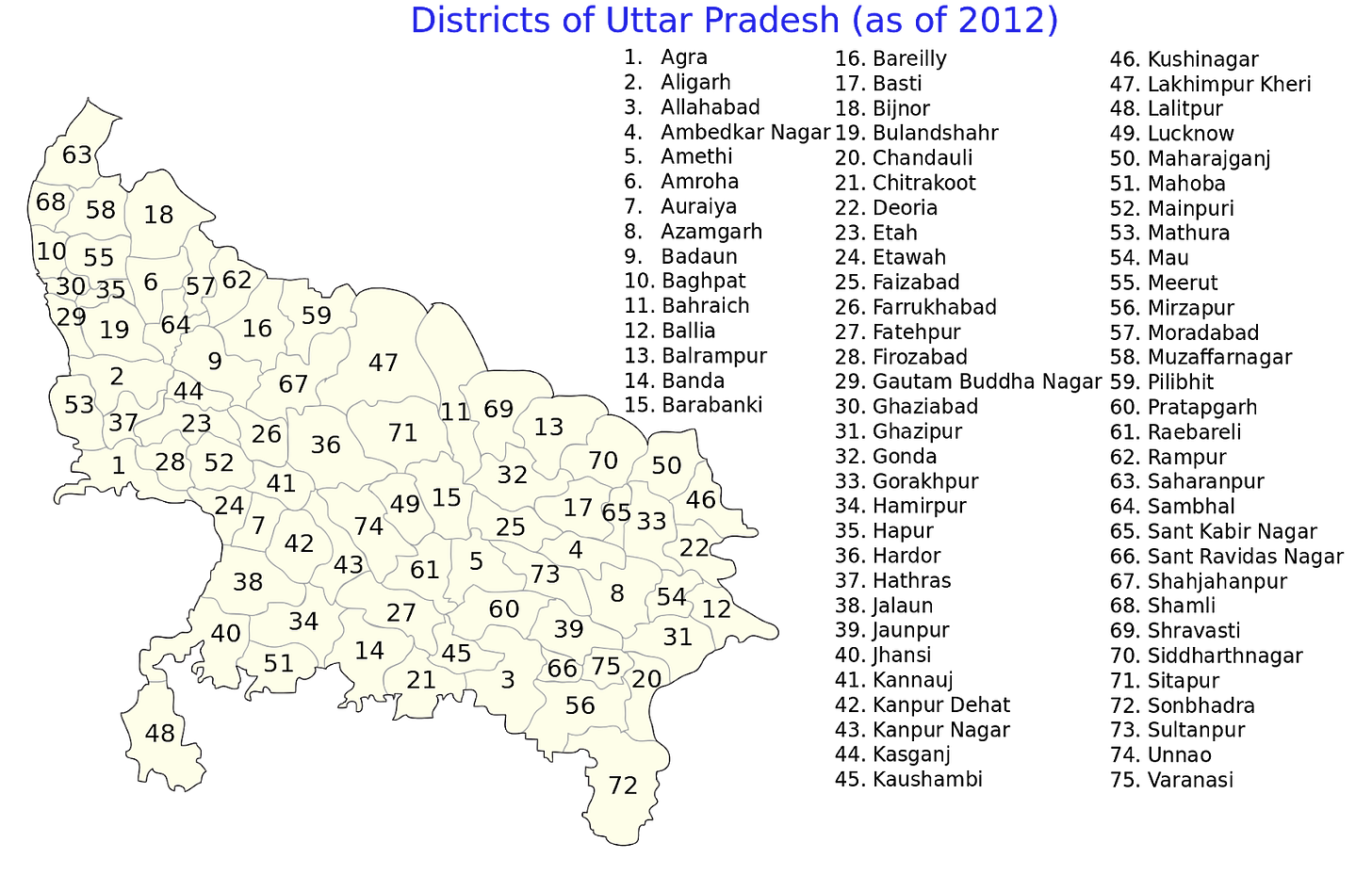

The state is further subdivided into districts.

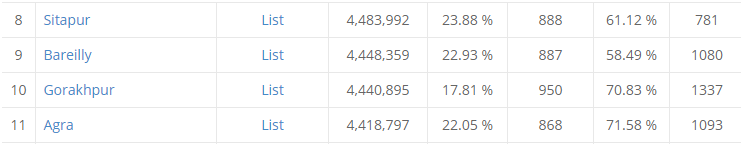

Most of these districts have more people than all of Oklahoma. Here are the top eleven. I brought the list down to No. 11 to capture Agra, home of the Taj Mahal plus 4.4 million people.

https://www.census2011.co.in/census/state/districtlist/uttar+pradesh.html

T

he trouble with teaching an online class is that I can’t petrify students by walking in, handing out this map of Indian districts, and asking everyone to label it neatly. Rats!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_districts_in_India#/media/File:India_districts.png

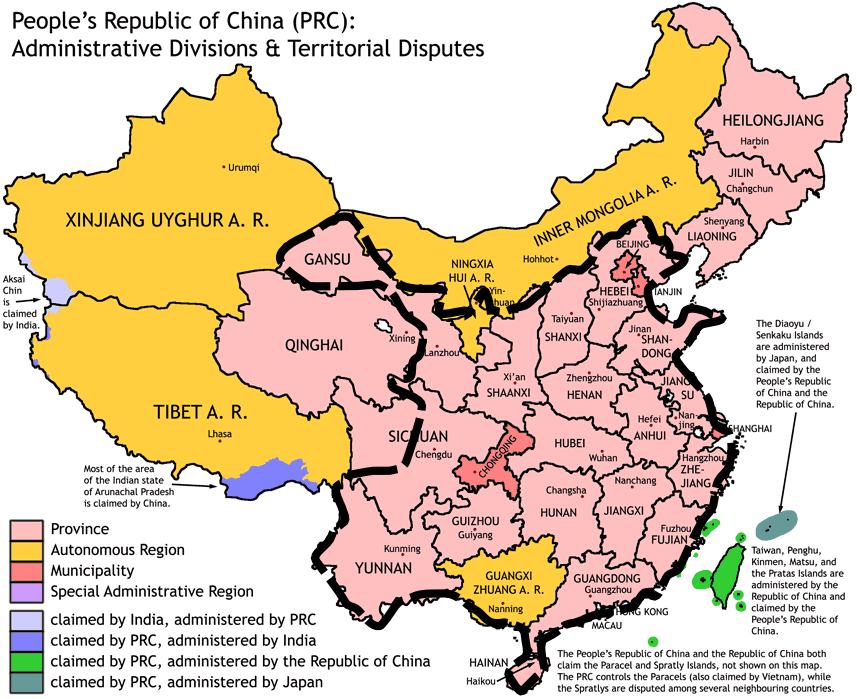

China takes a much harsher line of opposition to changing internal boundaries.

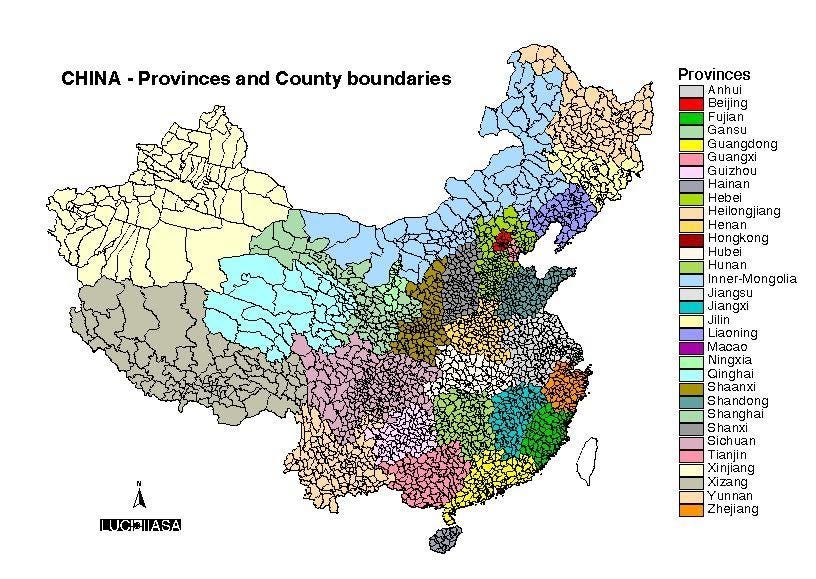

The heavy black line shows China Proper, the part of China that has been part of the Chinese state for most of the last 2000 years. The map shows or reminds us of three other things. First, Tibet, Xinjiang (which means “New Territories”), and Northeast China (formerly Manchuria) have been added to the Chinese state in the last two centuries. Most of these areas have been designated as Autonomous Regions because they have large populations of ethnic minorities such as Mongolians, Uighurs (or Uyghurs, as shown here—in either case, pronounced weegurs), and Tibetans. Second, the map shows in pink the country’s 23 provinces. Third, it shows in red the special status of Beijing, Shanghai, and Chongqing (formerly Chungking) as stand-alone municipalities.

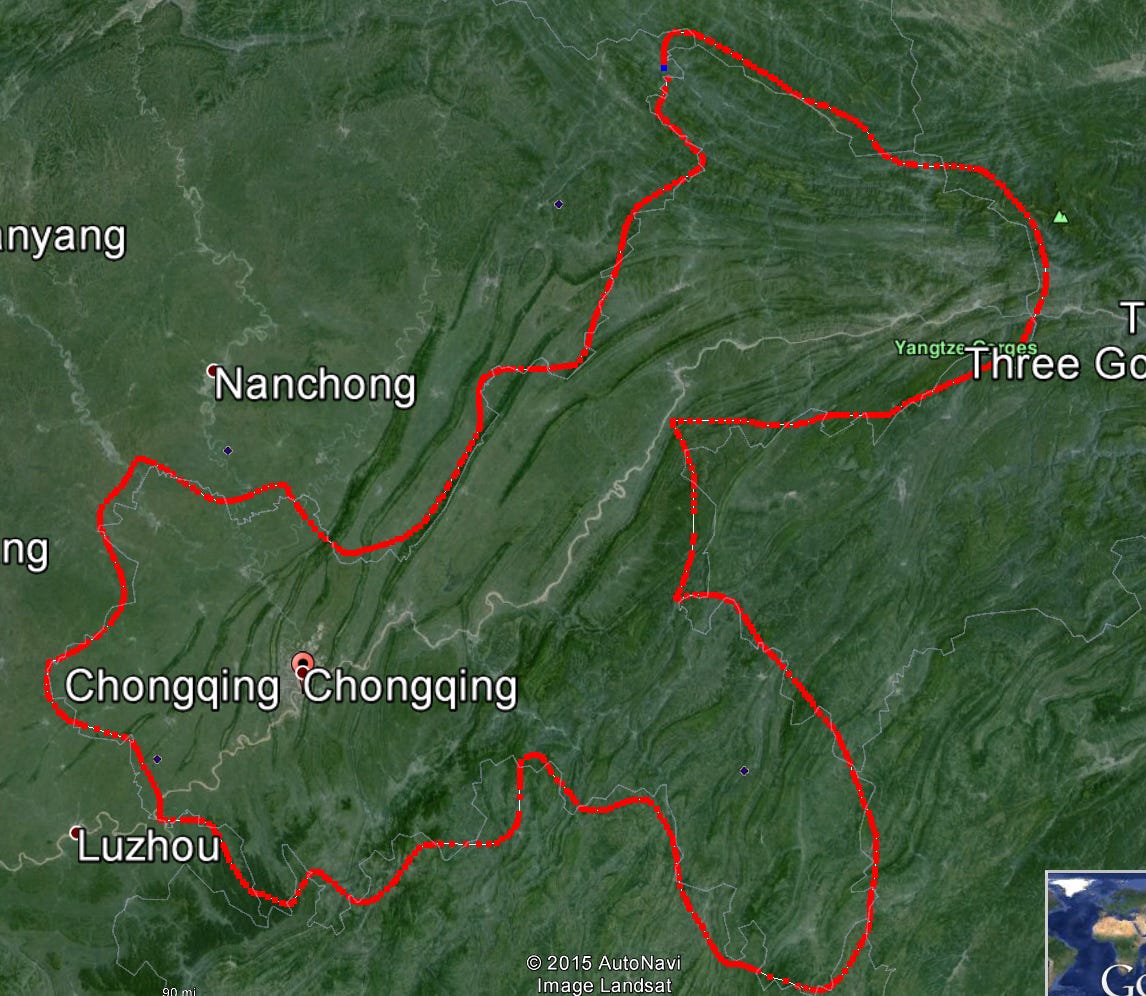

http://www.topchinatours.net/AboutChina/China-Overview/Politics.htm

Changes do occur. Here’s one: Chongqing, is a new municipality created around the old city of that name, which was previously part of Sichuan (formerly transliterated as Szechwan). Chongqing is sometimes ranked as the most populous city on earth, but that's because (as shown by the red line) its boundaries reach far into the countryside. Its maximum dimension is 270 miles across. Most of this is not urban, so calling Chongqing the world’s most populous city is a statistical gimmick.

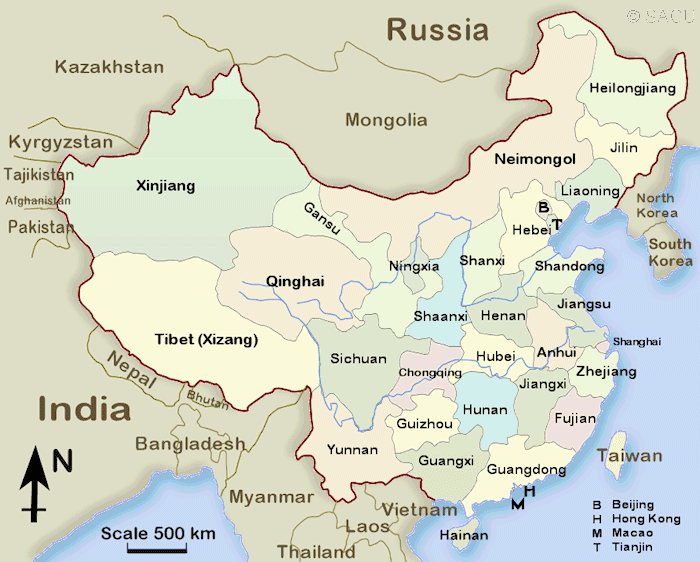

Should you bother learning any of these names? I bet that no U.S. president has ever known more than one or two. Still, ten Chinese provinces have more than 50 million people each, far more than live in California or Texas, and millions of Chinese have heard of those American states. I suppose you could argue that the Chinese watch American movies while Americans don’t return the favor. True enough, but with China’s growing power it’s probably only a matter of time before most Americans begin to learn at least some of these names.

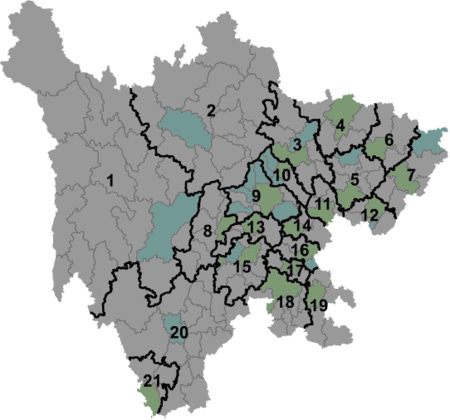

Do the provinces have subdivisions? Of course they do. Here is a map of the divisions of Sichuan. Division 9 is Chengdu, population 12 million people. Chengdu is further subdivided into 54 districts and 108 counties. China has about 1,400 counties.

Americans rarely know more than 20 counties by name. People in China know more. Reminds me of the cynical comment that war is God’s way of teaching Americans geography.

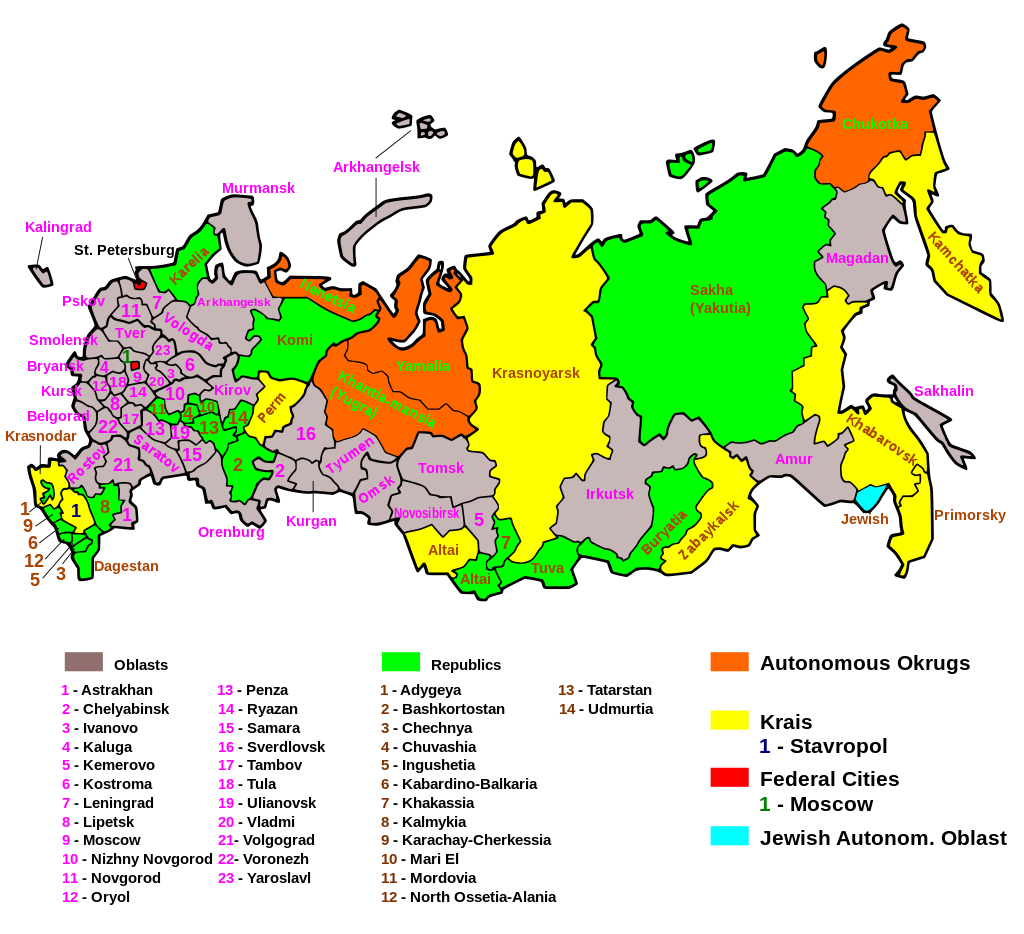

http://www.colorado.edu/geography/class_homepages/geog_3822_f09/images/adm_china_county.jpg

And just in case you think the maps of subdivisions in India and China are confusing, try this for size. Russia has 22 republics, 9 krais, 46 oblasts, 3 federal cities, 1 autonomous oblast, and 4 autonous okrugs. Not trying to drive you crazy, but here’s a little explanation. Oblast (gray here) can be translated as states. The Jewish Autonomous Oblast, in blue, is a Stalinist joke from 1934; with his death the Jewish populaton there began to decline from a peak of 30,000 in 1948 to under a hundred. Okrug (in burnt orange) translates as district, though the term is misleading because districts are normally smaller than states; not here. They’re big, though mostly empty and created for indigenous peoples. Krais (yellow) means frontier; they function like oblasts but even now are frontier regions and were even more so in czarist times. Perhaps krais is close to the English word “territory,” as in Canada’s Yukon Territory. That leaves the 22 republics (in green), areas with large ethnic populations, though Russians may still be the majority. The republics have the authority to designate their own official languages, and the largest of the republics has done so: the official languages there are both Russian and Sakha. The Republic of Sakha, by the way, is the largest subnational administrative area in the world: at 1. 2 million square miles, it’s twice the size of Quebec or about 17 times the size of Oklahoma.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subdivisions_of_Russia#/media/File:Russian_Regions-EN.svg

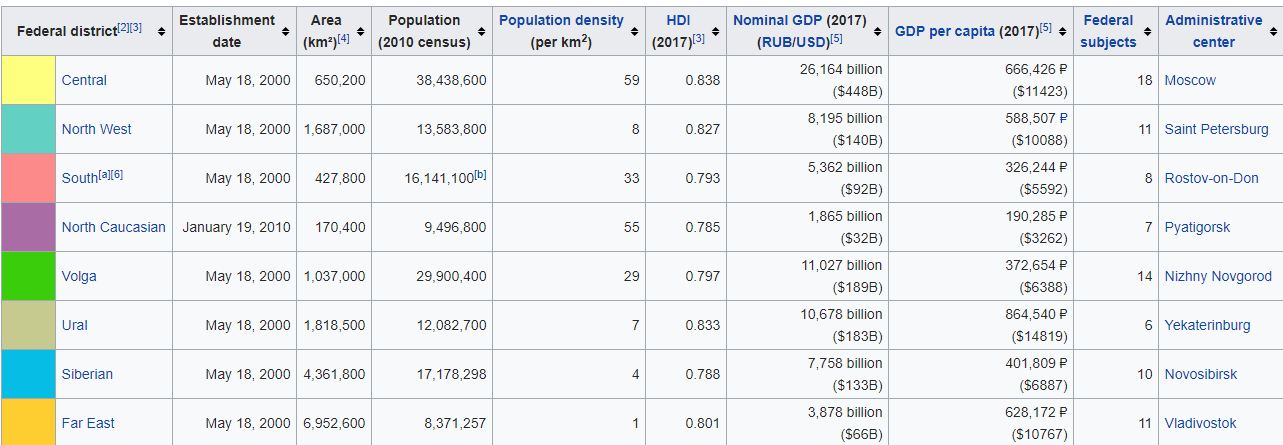

In case you wonder how a country as centralized as Vladimir Putin’s Russia can operate in such jurisdictional chaos, bear in mind that the country is also divided into eight federal districts. They were all established in the year 2000, except for the Crimean Federal District, established in 2014. Vladimir Putin has an official representative in each district. The representative is appointed by him and is responsible for carrying out Putin’s wishes. When he asks them to jump, I bet they say “How high?”